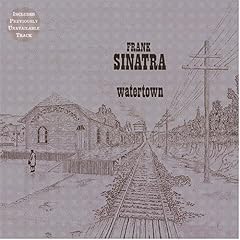

Frank Sinatra pretty much gave birth to the "concept album" in the early fifties, with discs like Swing Easy!, Songs for Young Lovers, and his greatest artistic triumph, In the Wee Small Hours.

And while his greatest moments on record came during his Capitol years (1954-1961), a lot of people seem to remember his mid-sixties Reprise years more fondly. Probably because a lot of his stuff wandered closer to "pop" music in those years, and can still be found on oldies radio now and then. And there's a ton of great stuff from that period, too. He was still flourishing creatively, with albums like The September of My Years (in which he confronts aging) and Francis Albert Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim (in which he tackles one of the world's greatest songbooks). And, of course, the Reprise years saw him release a string of classic hit singles: "It Was a Very Good Year" (#28 on the pop charts), "Strangers in the Night" (#1), Summer Wind (#25), "That's Life" (#4), "Somethin' Stupid" (#1), and "My Way" (#2). And, commercially speaking, he did have thirteen top ten albums between 1962 and 1969. Not bad in the era of the Beatles.

And while his greatest moments on record came during his Capitol years (1954-1961), a lot of people seem to remember his mid-sixties Reprise years more fondly. Probably because a lot of his stuff wandered closer to "pop" music in those years, and can still be found on oldies radio now and then. And there's a ton of great stuff from that period, too. He was still flourishing creatively, with albums like The September of My Years (in which he confronts aging) and Francis Albert Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim (in which he tackles one of the world's greatest songbooks). And, of course, the Reprise years saw him release a string of classic hit singles: "It Was a Very Good Year" (#28 on the pop charts), "Strangers in the Night" (#1), Summer Wind (#25), "That's Life" (#4), "Somethin' Stupid" (#1), and "My Way" (#2). And, commercially speaking, he did have thirteen top ten albums between 1962 and 1969. Not bad in the era of the Beatles.

One often overlooked Sinatra gem, Watertown, didn't have a hit single, and didn't even hit the top 100 (peaking at #101 on the Billboard charts in 1969). It's probably his most overt concept album, and I think it's brilliant. It's a true song cycle, detailing the breakup of a marriage, and the lingering impact on the singer. I think it's probably Sinatra's last hurrah as an interprative singer. The pain and loneliness is palpable, and it's hard not to buy into the concept when you hear Sinatra's broken lamentations on what he's lost. The album was generally written by Bob Gaudio, who was responsible for many of the Four Season's biggest hits.

One often overlooked Sinatra gem, Watertown, didn't have a hit single, and didn't even hit the top 100 (peaking at #101 on the Billboard charts in 1969). It's probably his most overt concept album, and I think it's brilliant. It's a true song cycle, detailing the breakup of a marriage, and the lingering impact on the singer. I think it's probably Sinatra's last hurrah as an interprative singer. The pain and loneliness is palpable, and it's hard not to buy into the concept when you hear Sinatra's broken lamentations on what he's lost. The album was generally written by Bob Gaudio, who was responsible for many of the Four Season's biggest hits.

The album starts with the title track, with swirling baroque pop insturmentation, as Sinatra tours the lonely town and ends at the train station in the rain, as his wife leaves him behind. The last sound we hear is the train pulling out of the station and heading away.

From there it segues into "Goodbye (She Quietly Says)," in which Sinatra struggles with what's happening to him, detailing his wife's calm "goodbye" in a coffee shop: "She reaches out across the table, looks at me and quietly says, 'goodbye.'" It's clear that she's made her mind up, and nothing this man can say will change it, and also that she has no real interest in explaining herself. It's a very real feeling track.

The third track is "For A While," which opens with a brief crescendo of horns, dovetailing into Sinatra trying to live his life without her, finding moments of happiness in the day-to-day, reinforced with the recurring "I forget that I'm not over you--for a while." He's still feeling the pain, but finding it easier to get along without her.

One of the more painful tracks comes next, in "Michael and Peter." The song starts with a quiet examination of his children, noting the things the boys have in common with he and his ex-wife. After a pause, things pick up, and take the form of a letter written to his ex, letting her know how the house looks, what the boys are doing, and how life seems to be going in the world she left behind.

"I Would Be In Love (Anyway)" is a summery tune, with some lovely woodwinds fluttering in the background. Sinatra reflects that even had he known how things would end up, he would have been in love with her, anyway. Sinatra really stretches his pipes on this one, insisting he wouldn't change what happened to him. Do we believe him?

"Elizabeth" comes next, and we learn the name of the ex, as he fondly (and sadly) remembers the early days of their courtship.

This theme continues in the next track, "What a Funny Girl (You Used to Be)," as he relates his positive and loving impressions of the girl he married. The song sounds as if it's being sung with a melancholy smile, and you understand what the man saw in the girl he loved. But always lingering in the background is the paranthetical, "You Used to Be," reminding us that, in his mind, at least, something changed in this girl he remembers so fondly.

The narrator begins to unravel a bit with "What's Now is Now," a direct confrontation with the reality of his relationship's collapse. It sounds as if he's discovered an infidelity, and, now assuming he knows "what really happened," is earnestly pleading that it doesn't matter, she can come home, and all will be forgiven. Sinatra sells the hell out of the sentiment here, and it's almost heartbreaking to hear him plead so openly for a reconciliation that the listener understands is really out of his hands.

With "She Says," the shortest track on the album, Sinatra relates what his wife is up to now without commenary, as if he's reading a letter to the kids. This is punctuated by the children's chorus of, "so she saaaaays" that rises up at times during the song. And then a dramatic kicker concludes the song, hammered home by a quick burst of strings: "She says...she says...she's coming home."

And so, next we find Sinatra waiting for "The Train." The sun comes out, the kids are coming home from school, and she'll be back soon. He details all the things he'll do right this time, and all the things he's changed since she "went away." Told largely in the present tense, we hear the excitement in his voice as he watches the train pull in, and the passengers disembark, and he looks for his wife, only to realize--she's not there. And our hopes are dashed with his. This may be my favorite track from the album. There's a very modern sounding cello line running under much of the song that adds an urgent weight to things, and the outro bubbles along, seemingly oblivious to this final crushing blow.

Finally, the album and song cycle conclude with "Lady Day." It's time, he realizes, for the rain to clear up, and for the sun to come out again. Of course, we get no real indication that's going to happen...

All in all, it's one of my favorite albums. It's definitely a product of the times in which it was released, and it's much more of a light pop album than almost anything else Sinatra did. But it works for me. If you're so inclined, dig it up.

From there it segues into "Goodbye (She Quietly Says)," in which Sinatra struggles with what's happening to him, detailing his wife's calm "goodbye" in a coffee shop: "She reaches out across the table, looks at me and quietly says, 'goodbye.'" It's clear that she's made her mind up, and nothing this man can say will change it, and also that she has no real interest in explaining herself. It's a very real feeling track.

The third track is "For A While," which opens with a brief crescendo of horns, dovetailing into Sinatra trying to live his life without her, finding moments of happiness in the day-to-day, reinforced with the recurring "I forget that I'm not over you--for a while." He's still feeling the pain, but finding it easier to get along without her.

One of the more painful tracks comes next, in "Michael and Peter." The song starts with a quiet examination of his children, noting the things the boys have in common with he and his ex-wife. After a pause, things pick up, and take the form of a letter written to his ex, letting her know how the house looks, what the boys are doing, and how life seems to be going in the world she left behind.

"I Would Be In Love (Anyway)" is a summery tune, with some lovely woodwinds fluttering in the background. Sinatra reflects that even had he known how things would end up, he would have been in love with her, anyway. Sinatra really stretches his pipes on this one, insisting he wouldn't change what happened to him. Do we believe him?

"Elizabeth" comes next, and we learn the name of the ex, as he fondly (and sadly) remembers the early days of their courtship.

This theme continues in the next track, "What a Funny Girl (You Used to Be)," as he relates his positive and loving impressions of the girl he married. The song sounds as if it's being sung with a melancholy smile, and you understand what the man saw in the girl he loved. But always lingering in the background is the paranthetical, "You Used to Be," reminding us that, in his mind, at least, something changed in this girl he remembers so fondly.

The narrator begins to unravel a bit with "What's Now is Now," a direct confrontation with the reality of his relationship's collapse. It sounds as if he's discovered an infidelity, and, now assuming he knows "what really happened," is earnestly pleading that it doesn't matter, she can come home, and all will be forgiven. Sinatra sells the hell out of the sentiment here, and it's almost heartbreaking to hear him plead so openly for a reconciliation that the listener understands is really out of his hands.

With "She Says," the shortest track on the album, Sinatra relates what his wife is up to now without commenary, as if he's reading a letter to the kids. This is punctuated by the children's chorus of, "so she saaaaays" that rises up at times during the song. And then a dramatic kicker concludes the song, hammered home by a quick burst of strings: "She says...she says...she's coming home."

And so, next we find Sinatra waiting for "The Train." The sun comes out, the kids are coming home from school, and she'll be back soon. He details all the things he'll do right this time, and all the things he's changed since she "went away." Told largely in the present tense, we hear the excitement in his voice as he watches the train pull in, and the passengers disembark, and he looks for his wife, only to realize--she's not there. And our hopes are dashed with his. This may be my favorite track from the album. There's a very modern sounding cello line running under much of the song that adds an urgent weight to things, and the outro bubbles along, seemingly oblivious to this final crushing blow.

Finally, the album and song cycle conclude with "Lady Day." It's time, he realizes, for the rain to clear up, and for the sun to come out again. Of course, we get no real indication that's going to happen...

All in all, it's one of my favorite albums. It's definitely a product of the times in which it was released, and it's much more of a light pop album than almost anything else Sinatra did. But it works for me. If you're so inclined, dig it up.

In a perfect world, this stuff would all come through soon, and I could breathe a little easier. Sadly, the world is not perfect, my friends.

In a perfect world, this stuff would all come through soon, and I could breathe a little easier. Sadly, the world is not perfect, my friends.